My research among emerging adults reveals that they often feel they aren’t treated as adults within the church community. While being called “Davy” as a child never bothered me, when I left for college, I hoped to leave that name behind. Sometimes, the easiest way for emerging adults to be treated like an adult is to leave their old world behind.

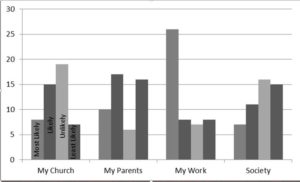

Emerging adults report that they are “most likely” to be treated as an adult at their workplace, while reporting that they are “unlikely”, and “least likely” to be treated like adults at their church, and in society.

William James, an American philosopher and psychologist, developed a theory of social selves which posits that an individual acts differently based upon the social situation and the expectations placed upon them. In some social contexts, emerging adults are expected to be an adult, while in other contexts, they are treated like a child. As emerging adults mature, our communication, actions, and words must display our support for their ongoing development.

Here are three ways you can allow your students to grow up:

1. Put on a new lens.

As adolescents grow up within a community, it is crucial to change our perspective towards them. One emerging adults states, “It seems at times that it is easier to meet new adults who recognize me as I am now than to be with adults who see me as I used to be.” (Parks 2000, 6) Emerging adults want people to understand they are not necessarily the same person they were in the past. One practical way is to realize that their interests, sports, and relationships might have changed, so we shouldn’t rely on their past experiences to relate to them. While some old bridges might remain, you must create new ways to relate to them during this phase of life. Focus on their maturity as they move towards adulthood by stepping back and viewing the individual from a new perspective.

As adolescents grow up within a community, it is crucial to change our perspective towards them. One emerging adults states, “It seems at times that it is easier to meet new adults who recognize me as I am now than to be with adults who see me as I used to be.” (Parks 2000, 6) Emerging adults want people to understand they are not necessarily the same person they were in the past. One practical way is to realize that their interests, sports, and relationships might have changed, so we shouldn’t rely on their past experiences to relate to them. While some old bridges might remain, you must create new ways to relate to them during this phase of life. Focus on their maturity as they move towards adulthood by stepping back and viewing the individual from a new perspective.

2. Raise Expectations

Individuals read social settings and often conform to the expectations placed upon them. When I was thirty, I went on a mission trip with a group of older adults to Africa. After a few hours, I noticed that as the “youngster” of the group, I was expected to be funny and childish. Feeling the pressure, I conformed and took on these behaviors. Discuss appropriate expectations for EA’s within your community and seek to clearly communicate them. Here is a link for some practical ideas on how to raise expectations in your community.

3. Encourage Autonomy.

A utonomy is the ability to make decisions and deal with the consequences of them independently. As mentors, we must allow EA’s to have the freedom to choose beliefs and behaviors even when we do not agree with them. Avoid shaming EA’s for their choices or conveying an “I told you so” attitude. If you feel led to confront an issue, deal directly with emerging adults rather than work through parents. We must remember that “as a young adult becomes more fully adult, mentors become peers” (Parks 2000, 84), and be careful to change the boundaries that we once held as our relationship changes throughout the years.

utonomy is the ability to make decisions and deal with the consequences of them independently. As mentors, we must allow EA’s to have the freedom to choose beliefs and behaviors even when we do not agree with them. Avoid shaming EA’s for their choices or conveying an “I told you so” attitude. If you feel led to confront an issue, deal directly with emerging adults rather than work through parents. We must remember that “as a young adult becomes more fully adult, mentors become peers” (Parks 2000, 84), and be careful to change the boundaries that we once held as our relationship changes throughout the years.

As Parks writes, “For each of these young adults—and, as a consequence, for all of us—there is much at stake in how they are heard, understood, and met by the adult world in which they are seeking participation, purpose, meaning, and a faith to live by.” (Parks 2000, 3) EA’s want to be welcomed into our community not because of who they once were, but for who they are now, to be approached, heard, and understood as adults. It may take time for both sides to redevelop this “new” relationship. But establishing new boundaries and a new way to relate is crucial if we are going to allow these young adults to grow up.

Dr. G. David Boyd is the managing director of EA Resources – a non-profit designed to equip parents and churches to engage emerging adults. He is also the founder of the EA Network – a community of people who serve and love emerging adults.

Dr. G. David Boyd is the managing director of EA Resources – a non-profit designed to equip parents and churches to engage emerging adults. He is also the founder of the EA Network – a community of people who serve and love emerging adults.

Parenting emerging adults while rewarding is sometimes a difficult job. Parents often feel isolated because their words might embarrass either themselves or their adult children. This is especially true in the church where parents often feel as if they have failed. Corey writes, “Sadly, our churches often forget that one of the primary roles of the body of Christ is to be a hospital for sick and broken people.”

Parenting emerging adults while rewarding is sometimes a difficult job. Parents often feel isolated because their words might embarrass either themselves or their adult children. This is especially true in the church where parents often feel as if they have failed. Corey writes, “Sadly, our churches often forget that one of the primary roles of the body of Christ is to be a hospital for sick and broken people.” Corey is the founder of

Corey is the founder of